Exhibition opened on October 5, 2016 and marked the 75th anniversary of the invasion of Hong Kong.

The Defence of Hong Kong was the first battle of the Second World War in which Canadians fought. It involved two under-prepared Canadian battalions with little to no fighting experience.

The fight ended in 18 days … but the nightmare would last almost four more years.

In September 1941, Hong Kong was still a British Colony. But it was now surrounded by the Japanese who occupied key areas of China.

After a request from British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Canada offered up two infantry battalions (1,975 personnel) to serve as a deterrent against a possible Japanese invasion of the territory.

The Royal Rifles of Canada (from Quebec) and the Winnipeg Grenadiers (from Manitoba) were untested in battle. Their leaders were led to believe there would be time to prepare. Some of the soldiers thought they were simply going to do garrison duty. One man even brought his golf clubs.

On December 8, 1941, a few hours after Pearl Harbor was bombed, the Japanese attacked Hong Kong.

Although the Canadians stood alongside British and Indian soldiers, as well as members of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps, the defenders were out numbered four-to-one and were poorly equipped. The fighting was fierce, and each day the Allies were pushed back and eventually were cornered on Hong Kong Island. Approximately 290 Canadian soldiers died in the fighting.

Many soldiers were executed by the Japanese even after they had surrendered their posts. Civilians, medics and even hospital patients were massacred and raped as the Japanese stormed the territory.

The fighting ended on Christmas Day, when the Governor of Hong Kong finally surrendered the colony after much bloodshed.

Thus began another battle – the fight to simply survive the extraordinarily harsh conditions in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps and Japanese occupation in general. Almost 1,700 Canadians spent the next four years as POWs. They were joined by thousands of other Allied soldiers and residents of Hong Kong. The POWs endured starvation; beatings; manipulation; back-breaking work for up to 12 hours a day; diseases that went untreated (such as malaria, diphtheria and infections); and filthy living conditions. During incarceration, another 264 Canadians died.

Of the 1,975 Canadian personnel who came to assist Hong Kong, approximately 1,050 either died or were wounded by the time the war ended: a 50 per cent casualty rate.

BILL CHONG (AGENT 50)

William “Bill” Gun Chong was born in Vancouver in 1911. He happened to be in Hong Kong, dealing with his late father’s estate, when the Japanese invaded.

Chong was enraged by the atrocities and killings he witnessed as the Japanese took control of the colony. He was determined to fight back.

Bill Chong (BAAG Agent 50)

Escaping to China, Chong initially sought to become a guerrilla fighter. Instead, he was persuaded to join the British Army Aid Group (BAAG) of the British Military Intelligence Section, MI-9. He became a spy and was assigned the code name “Agent 50.”

Chong spent five years gathering intelligence; relaying messages; ferrying much-needed medical supplies to secret field hospitals; and helping downed airmen and POWs escape. He usually worked alone, and would often walk 50-80 kilometres a day dressed as a Chinese peasant and wearing straw shoes. He did not sleep in a real bed for almost four years.

He also lived in constant fear of being discovered. He was captured three times and narrowly escaped each time. Despite those close calls, Chong continued to risk his life and today is credited with saving the lives of hundreds of Allied airmen and POWs.

DR. RAYMOND LEE

Born in 1911 in Toishan, China, but raised in Canada, Dr. Raymond Lee had recently completed his medical degree at Hong Kong University when the invasion happened. The Japanese needed his medical expertise and desperately tried to recruit him, but Lee refused and escaped to free China. There, Lee was invited by Colonel Lindsay Ride to join BAAG and become their lead physician in charge of establishing and operating medical outposts. (Ride, an Australian who had escaped a POW camp, had been an associate of Lee’s at Hong Kong University.)

While Lee’s original assignment was to focus on medical treatment for escaped POWs and British Army and BAAG personnel, it did not take long before his patient list ballooned. As war raged on, Lee expanded his services to Chinese army personnel (both nationalists and communist guerrillas). As well, each day his team would treat hundreds of ordinary Chinese residents who were sick from disease and starvation or were badly injured in the frequent air raid bombings.

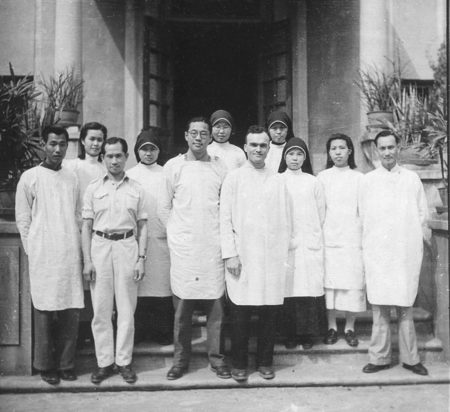

Dr. Raymond Lee (5th from left) with members of his medical team. Third from left is Bill Chong.

Besides running medical outposts, Lee also established several congee kitchens to help address the severe malnutrition of civilians. Despite working in sometimes crude conditions, and with many untrained staff, Lee’s medical expertise and leadership skills helped saved thousands of lives.

WILLIAM LORE

William K. Lore, born in Victoria in 1909, was the first Chinese officer in the Royal Canadian Navy. In fact, he was the first officer of Chinese descent to serve in any of the navies of the Commonwealth.

Late in the war, Lore was assigned to British Pacific Fleet. Pulling into Hong Kong Harbour aboard the Swiftsure on August 30, 1945, Lore was handpicked by Rear Admiral Cecil Harcourt to be the first British Officer to step ashore onto liberated Hong Kong soil. The next day, Lore was tasked to liberate the notorious Sham Shui Po POW camp. After a short, intense stand-off with the Japanese guards at the prison gates, Lore found his way into a dirty, ramshackle barrack, housing dozens of sick and emaciated Canadians. It was a reunion that would be forever etched into Lore’s memory.

William Lore circa 1943

In his diary, Lore described the scene:

I could see 20 or 30 officers in ragged remains of uniforms looking at me … without a sound. I then walked a few steps towards them and said “I am a Canadian naval officer, and I am here to liberate you guys. Aren’t you glad to see me?”

A few came towards me … gazed at my cap badge …and then exclaimed “You are real! We are saved!”

Then came a rush towards me, with tears and shouts, which brought further POWs down rickety wooden stairs from the upper floor of the building.

I have never seen so many men in tears together. But they were “happy tears.” In fact, I was in tears myself because they were like skeletons and I realized that the young happy-go-lucky boys of less than four years ago, had now become old men…

William Lore, August 31, 1945.

WILLIAM POY

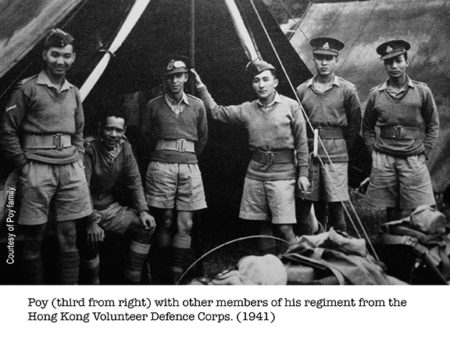

Born in Australia in 1907, William Poy ventured north to the British colony of Hong Kong while still in his 20s.

He adapted quickly to his new home. Poy became a successful amateur jockey and, through participation in the “sport of kings,” was introduced into British Colonial Society. He joined the Freemasons and eventually became Right Worshipful Master of his chapter lodge in Hong Kong. He also married, had two children and began a promising career at the Canadian Trade Commission.

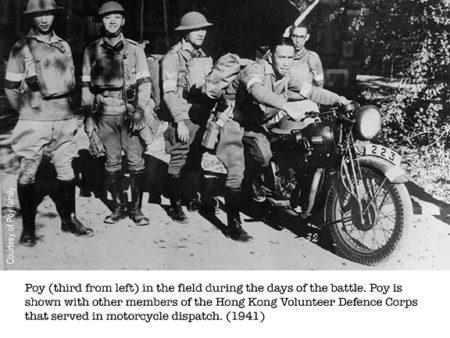

When Japan attacked the colony, Poy volunteered to be a motorcycle dispatch rider for the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps. He traversed dangerous roads — dodging bombs, shelling and mortar fire — in order to deliver vital communiques. Poy survived his missions and was later decorated by the British for his courage and tenacity.

Photo courtesy of Lore family

Photo courtesy of Lore family

Months after Hong Kong fell, the warring governments negotiated an exchange of Allied for Japanese nationals. Just hours before the Red Cross ship with Allied nationals was to set sail, Poy got word that he, his wife and two young children were on the list to leave for Canada. They were accepted into Canada despite the fact the Chinese Exclusion Act was still in effect. (This Act, instituted in 1923, essentially banned immigration of Chinese into Canada.)