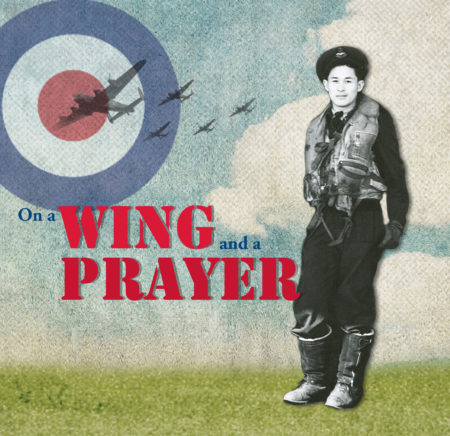

On a Wing and a Prayer opened in the Fall of 2017. The exhibition told the remarkable stories of the Chinese-Canadian Air Force men who fought, died and survived some of the most harrowing situations of the Second World War.

When the Second World War erupted in 1939, aviation was still a novelty. (The first successful flight of the Kitty Hawk happened only in 1903). Flying was romanticized due to the exploits and publicity surrounding aviators such as Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart.

Most Canadians had never sat in a plane, much less fought an enemy from a moving aircraft. But the allure of the skies drew many young men to Air Force enlistment offices, including Chinese Canadians.

In the early years, most Chinese Canadians were turned down for any role in the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) because they were not Caucasian. But as war raged on and expanded, more men were needed and Chinese Canadians were given a chance to prove their mettle.

They were trained for roles as pilot, or navigator, bomb aimer, wireless operator, engineer, gunner, mechanic and trainers.

They were assigned to every Command: Bomber Command; Fighter; Coastal; Transport; and Training. And they found themselves stationed around the world (i.e. Europe, South East Asia, China) and at home in Canada.

For some, especially those who took to the air in Bomber Command, the days involved long hours of boredom punctuated by moments of absolute, sheer terror. Some men took their last breath over the skies of Europe.

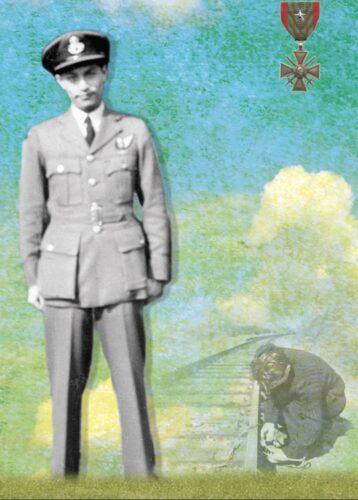

SURVIVING THE FALL

A few Chinese Canadians died in bombers. But at least one survived a doomed flight.

P/O Kam Len “Douglas” Sam was a rear gunner with RCAF’s 426 “Thunderbird” Squadron. He had 27 missions under his belt.

In the wee hours of June 29, 1944 – having just completed a bombing run targeting the rail yards at Metz, France – Sam’s Halifax was attacked by German fighters. A fuel tank exploded: the craft became a flying inferno. Sam bailed out.

Rather than leave occupied France, Sam was asked by MI-9 and the French Resistance to stay and help with the escapes of other Allied airmen. He was provided with clothing and forged papers that identified him as an Asian student trapped in France by the German occupation.

The ruse worked: using his high school French, Sam successfully bluffed his way out of several Gestapo roundups. Meanwhile, he helped the Resistance with espionage and sabotage operations until the Americans finally entered Rheims in early September 1944.

Among the many awards for his service, Sam was bestowed with France’s Croix de Guerre with Silver Star.

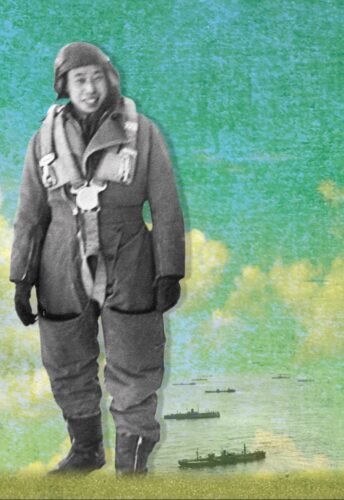

HUNTING U-BOATS

German submarines, known as U-boats, were a silent and deadly threat in the Atlantic during the war. Lurking beneath the surface, and sometimes operating in “wolf packs,” they were adept at hunting and destroying merchant ships. Thousands of lives and millions of tons of supplies, critical to Britain’s survival, were lost in the cold, dark sea due to U-boats.

Monty Lee was trained by the RCAF to be a Bomb Aimer. Assigned to Coastal Command and stationed in Labrador, he was the only aircrew of Chinese descent. His job was to fly above the convoys and help patrol and protect the merchant ships through to the mid-Atlantic.

Lee spent many long hours in the cramped nose of his bomber (usually a Halifax or a Wellington). His eyes were glued to his binoculars as he surveyed the vast ocean for any tell-tale signs of a U-boat. Lee had to be ready at a moment’s notice to guide his pilot and then aim their bomb on the fast-moving sub.

As the war progressed, the number of ships lost on the Atlantic declined. Several factors played a role, but certainly many a merchant seaman owes his life to airmen, like Lee, who helped prevent U-boats from making a successful attack.

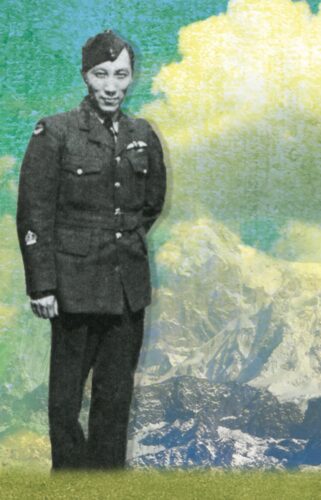

FIGHTING IN A SPITFIRE

Fighter pilots like Harry Gong, were often regarded as the rock stars of the air force. Although they flew with a squadron of other planes, in reality they were solo fliers: strapped alone in their cockpits performing aerial acrobatics while chasing down enemy planes or avoiding attacks.

Gong had the rare honour to fly the celebrated Spitfire with its powerful Merlin engine.

After training on Hurricanes in Canada, he was posted to the RAF Third Tactical Air Force in India (South-East Command). His role was to provide close air support to Britain’s 14th Army during the Burma campaign. It meant taking off and flying his Spitfire in all types of unpredictable weather and treacherous conditions that would normally have kept planes grounded. An additional fear for Gong was the knowledge that if he was shot down over the dense jungle, survival would be next to impossible.

Gong was the only Chinese Canadian known to have been a fighter pilot for the RCAF or RAF.

Unfortunately, he never shared his war experiences with anyone.

FLYING THE HUMP

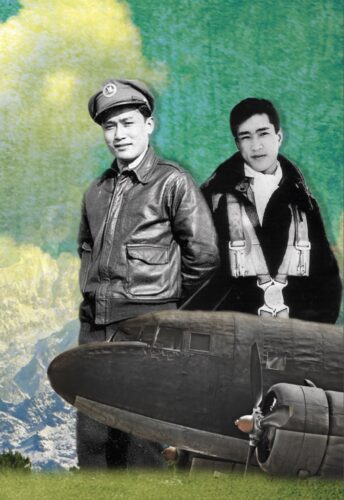

Cedric (below left) and Albert Mah were brothers who volunteered to fly one of the most dangerous routes in the world: between China and India over the Himalayan mountains. Known as “flying the Hump” – a route also dubbed the “graveyard of the air” – it involved an almost 1,800-kilometre round trip plagued by extreme cold; dangerous and variable weather; and wind gusts up to 320 kph. Most of the area was unmapped and pilots had to gauge the height of mountain peaks.

Hired by China National Aviation Corporation (CNAC), the Mah brothers flew unpressurized C-47s and C-46s. In an effort to aid the Chinese war effort against the Japanese occupiers, the Mahs transported strategic and often volatile materials into China (e.g., ammunition, TNT and gasoline). They then returned to India loaded down with lead, zinc or mercury.

With all that cargo, their planes often had trouble flying high enough to clear the peaks, so the Mahs had to weave a path through the mountains. At one point in the war, in order to avoid encountering Japanese fighters along the route, they both were forced to fly at night and in bad weather.

The official CNAC tour of duty was 80 round trips. Cedric (left) managed 337 trips. Albert, who was the first brother to join the Chinese airline, flew an astounding 420 successful missions. Both brothers had many amusing tales about the

“ups and downs” of those harrowing journeys.

THANK YOU TO OUR EXHIBITION SPONSOR: