Young Ming (James) Wong was born on August 7, 1920. He was one of a family of 10 children whose father ran a grocery store in Vancouver. At a time when many young men dropped out of school early to earn a wage, Wong stayed in school and graduated from Grade 12.

He was smaller than average and rather slight, but what he lacked in physical prowess Wong made up for with his intelligence. He loved to read and was considered bright and articulate. Prior to joining the war effort, Wong worked his way up to be a bookkeeper for the US Army Engineers in Prince Rupert, British Columbia.

The Canadian Army recruiter who first interviewed Wong was quite impressed by the lad as evidenced by the comments made in Wong’s service file.

“Has very high learning ability. In view of his civilian experience as a warehouseman and bookkeeper, he seems suitable for service… He possess leadership ability and was foreman of a Chinese crew in civilian life. His manner is co-operative, alert and self confident. Ought to adjust well and become a valuable soldier. Suitable for enriched training during basic.”

Wong was sent off for basic training in the fall of 1944. In February 1945, he was withdrawn from basic training and assigned “special duties” — this was code for recruitment to Force 136. He became one of almost 150 Chinese Canadians who were slated to be trained for secretive, dangerous missions in the jungles of Southeast Asia.

Force 136 came under British Intelligence –Special Operations Executive. Not part of the “regular armed forces” these men would be assigned operations behind Japanese lines in Southeast Asia. Force 136 men were trained in guerrilla warfare and jungle survival techniques. Each man was to specialize in a particular skill (demolition, wireless, interpretation) that would make him useful in a small, mobile, self-sufficient team. The plan was to parachute these small teams into Japanese occupied territory. There they would survive on their own skills; find and train local resistance fighters; and then assist with sabotage and espionage of the enemy.

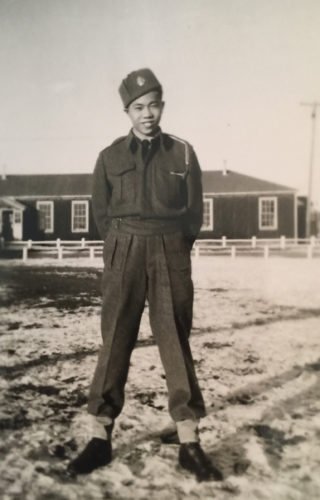

Young Ming (James) Wong of Force 136. Circa 1944 Vancouver.

The young Chinese Canadian men were told they had a 50-50 chance of survival. And if captured, they would likely be tortured and executed by the Japanese. Consequently, anyone going on an ops mission was given a cyanide capsule to keep in their pocket and instructed to bite on the capsule if captured.

Wong was sent to India for his commando training. He was joined there by his cousin Donald Sung. We do not know if Wong was sent on any assignments before the war in the Pacific ended as he seldom shared his memories with his family.

We do know that many isolated Japanese units did not surrender until weeks later. However, once the atomic bombs were dropped, most of the young men of Force 136 were quickly informed that there services were no longer needed by the British and plans were made to send them home.

It was a long boat ride back to England where the famous photo below was taken. After a short stay in the UK, the young men hopped onto another ship bound for Halifax. Once in that port, Wong and most of the Force 136 members boarded a train back to the West Coast of Canada.

Force 136 men in England awaiting repatriation to Canada. Young Ming James Wong is back row, second from left. His cousin, Donald Sung, is front row middle. (Library and Archives Canada)

Wong returned to Vancouver and eventually married and had three children.

His most successful business venture after the war was a restaurant he started in Kerrisdale, a tony neighbourhood on the West side of Vancouver. The Miramar Chinese Restaurant was one of the first, high-end Chinese restaurants in that part of the city. It is still there today, in it’s original form, although it has now been renamed The Golden Ocean.

Wong passed away peacefully on July 7, 2016 in Coquitlam. He was just shy of his 96th birthday.

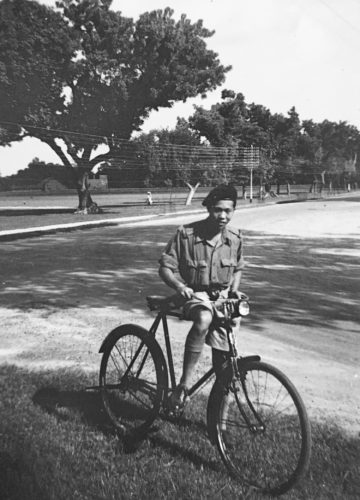

Young Ming (James) Wong in India

Young Ming (James) Wong in India with a bicycle