Roger Kee Cheng was a captain in the Canadian Army and has the distinction of being the first Chinese Canadian officer in Canada.

He is best known for his work with Force 136 – a unique unit trained as commandos and destined to be dropped behind enemy lines in South East Asia. Their mission would be to seek out, train and support local resistance fighters.

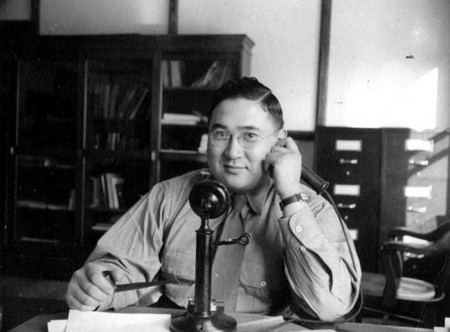

Roger Cheng

Cheng was among the very first group recruited to Force 136. He was one of 13 Chinese Canadians hand-picked by Britain’s Special Operations Executive (i.e., British Intelligence) and trained in commando-style warfare.

These first recruits became known as the “Operation Oblivion” men. They were taken to a secluded spot on Okanagan Lake (now known as Commando Bay) and put through extremely rigorous training. They learned stalking; silent killing; demolition; silent swimming; and jungle survival techniques among many other things.

Operation Oblivion group. Roger Cheng is front row, fourth from the right.

The group was initially slated to be dropped into Japanese-held areas of China. Their mission would be to link up with Chinese resistance fighters (many of who were communist rebels) and help aid in training, sabotage and espionage.

The plans for China were scuttled when the Americans took over control of the war in the Pacific.

So instead of going to China, the Operation Oblivion team was shipped to Australia for further training and to await their assignments.

Cheng was the first to be assigned a mission. In March 1945, he was tapped to lead a team into Japanese-occupied Borneo. On his team were four other Chinese Canadian men: Roy Chan, Louey King, Norman Low and Jim Shiu. They were supported by seven Chinese soldiers.

They were asked to contact and befriend Dyak headhunters; provide equipment and training; and assist with sabotage of Japanese supply lines and equipment.

Later the team was asked to seek out isolated Japanese units and force them to surrender. Cheng and his men also located and liberated POW camps and arranged for the transfer of prisoners. As the war ended and Borneo was chaotic due to the lack of a civilian government in place, Chen and his team took on roles to maintain order: organizing tribesmen into local security forces; patrolling rivers; and preventing revenge massacres of Japanese troops and suspected collaborators.

After the war, Cheng and his men were sworn to secrecy, so it took a long time before the public and their families understood the unique and dangerous experiences they had had as soldiers. But these men proved their loyalty to Canada and their willingness to die for a country that had not recognized them as full citizens.

Two years after the war ended, Chinese Canadians were granted the right to vote. And the hated Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned immigration from China since 1923, was repealed by the federal government.

Cheng passed away in 1990.

Listen to an interview he did with University of Victoria.

Roger Cheng post WWII