Born in 1911 in Toishan, China, but raised in Canada, Dr. Raymond Lee had recently completed his medical degree at Hong Kong University when, on December 8, 1941, the Japanese invaded Hong Kong.

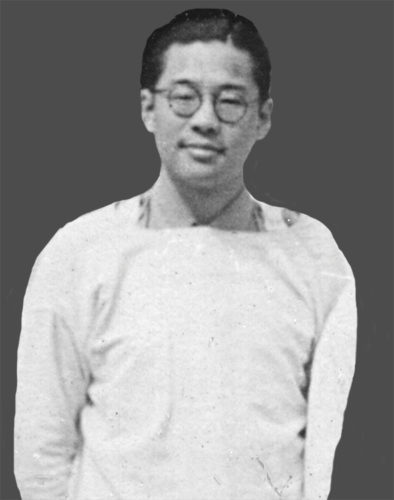

Dr. Raymond Lee (BAAG physician)

The Japanese desperately needed his medical expertise and tried hard to recruit him, but Lee refused. Knowing he would be thrown in jail for not cooperating, Lee escaped to free China. There, he was quickly recruited by Colonel Lindsay Ride to join the British Army Aid Group (BAAG). This innocuous sounding organization was supposed to provide assistance to escaped POWs and soldiers, but was also a cover for espionage activities in the region.

Lee was made one of BAAG’s lead physicians in charge of establishing and operating medical outposts in Free China. (Ride, an Australian who had escaped the Sham Shui Po POW camp, had been an associate of Lee’s at Hong Kong University.)

While Lee’s original assignment was to focus on medical treatment for escaped POWs and British Army and BAAG personnel, it did not take long before his patient list ballooned. As war raged on, Lee expanded his practice to Chinese army personnel (both nationalists and communist guerrillas). As well, each day his team would treat hundreds of ordinary Chinese residents who were sick from disease and starvation, or who were badly injured in the frequent Japanese air raid bombings.

Over the 3.5 years of Japanese occupation, Lee set up and supervised numerous medical outposts throughout China. Often these makeshift hospitals were located in abandoned and bombed out schools and churches where there was no heat, light or even glass on the windows.

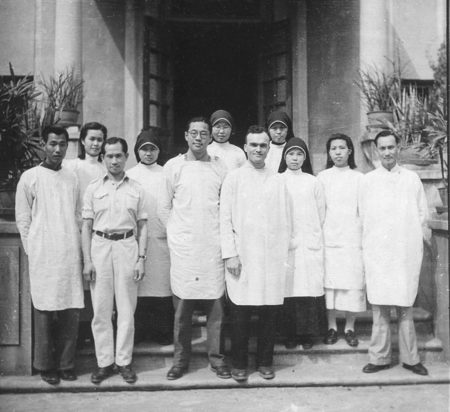

Dr. Raymond Lee (5th from left) with members of his medical team. (Bill Chong, Agent 50, is 3rd from left.)

Life saving drugs were valuable … and rare … and had to be secretly smuggled in to the field hospitals by BAAG couriers. Penicillin was especially coveted and was often stolen before it reached the medical clinics. So Lee was placed in charge of the distribution of penicillin: he ensured the valuable medicine destined for BAAG hospitals did not end up on the black market.

Later, to save civilians who were starving, Lee set up a number of soup/congee kitchens.

Despite working in sometimes crude conditions, and with many untrained staff, Lee’s medical expertise and leadership skills helped saved thousands of lives.

Lee oversaw and treated hundreds of cases every day. Despite the fact many of his staff were not trained, the success rate was astonishing. As Lee described it later…

“There was hardly an afternoon that we didn’t have 2 to 6 surgical operations going on. Besides, there was one day in a week devoted entirely to dental extractions. In spite of the fact that most of the personnel were untrained there was no record of death in the operating theatre, and the post-operative death was less than 1%. And about a third of them were major procedures …”

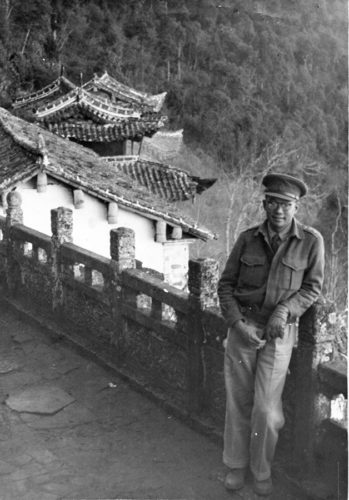

Dr. Raymond Lee, somewhere in China during WWII.

Lee survived the war. And even years after the conflict ended, his exploits and contributions were well known in Hong Kong and China.

Later in life, Lee returned to place of his youth: he died in Vancouver, Canada, in 1972.